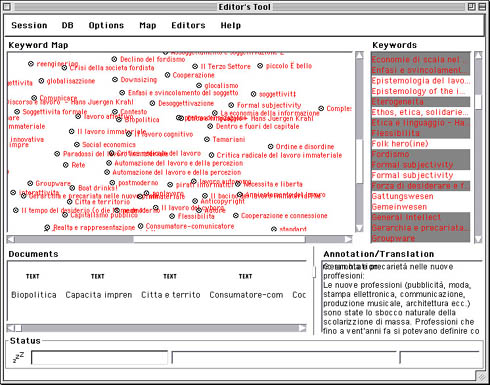

collaborative interface

1999

Editor: Enzo Rullani Economist

- Laurea in Economia e Commercio, Università Ca’ Foscari, Venezia - Campi di specializzazione: - Economia della conoscenza. Transizione verso il postfordismo. - Internazionalizzazione. - Reti e distretti. - Servizi e tecnologie della comunicazione. bibliography: - "Più locale e più globale: verso una economia postfordista del territorio", in: Bramanti A., Maggioni M.A. (a cura di), La dinamica dei sistemi produttivi territoriali: teorie, tecniche, politiche, Angeli, Milano, 1997 - Impresa transnazionale ed econonomia globale, Nis, Roma, 1997 (con R. Grandinetti) - Dal fordismo realizzato al postfordismo possibile: la difficile transizione, in: Romano L., Rullani E:, Il postfordismo. Idee per il capitalismo prossimo venturo, Etas Libri, Milano, 1998 - Percorsi locali di internazionalizzazione, a cura di G: Corò e E. Rullani, Angeli, Milano, 1998 ",Il nuovo ruolo della piccola impresa" in Feltrin P. (a cura di), Quale società della piccola impresa, Nis, Roma, 1997.

keyword 125 - Immateriale | Immaterial | Editor: Enzo Rullani Immateriality is a functional kind of concept: a form (F) is an immaterial resource if there is a functional equivalence between the material things that can be its support. If the support is indifferent, indeed, if the functional equivalence between F as mounted on a given support and F as mounted on a different one, proves that the contribution to production comes from F, not from the support. The immateriality of knowledge depends on its transferability from a material support to another one, thus it doesn´t have anything to do with reproducibility: an immaterial resource reproduces a process in a functionally equivalent way by changing its own material supports. Being the knowledge of reproducibility, science is immaterial by definition: it would not be possible to reproduce the effect of a scientific law if there were no functional equivalence between the supports used both in laboratories and in real life. In the same way, a machine contains immaterial knowledge because it can be reproduced: what counts is not the steel support, but the design and engineering knowledge that shaped it. The shape provides the constant, which is (potentially) the same in all machines of the same kind, while steel is the functional equivalent, the perfectly replaceable support. Again, a record contains the sound shape of a voice, and the support has no economic importance, because it is functionally replaceable. But... is the brain functionally replaceable? At this point, the notion of immateriality gets shakier, because each brain is unique, it does not reproduce a given form; rather, it generates original forms that are not completely transferable to other brains (by codification/interpretation). Yet this problem (the difference between the human brain and such a functionally equivalent support as a computer) is just the tip of the iceberg. Knowledge elaborated by humans has a personal and cultural mark: every cognitive event is a part of life and consciousness, therefore it is an unique, irreproducible fluxus of experience. There is no longer any immateriality, once we consider the contextual quality of knowledge by learning. Being embedded in its own context, knowledge cannot be transferred nor reproduced in compliance with the principles of functional equivalence, unless knowledge is constructed ad hoc, by a process of de-contextualization.

Editormap Enzo Rullani